MyRadar

News

—

Calling All Pilots — The Hidden Meteorological Dangers of Aviation

by Will Cano | News Contributor

8/15/2023

Whether you are a private pilot aiming for your Pilot's License or a professional pilot chartering flights across the globe for American Airlines, you know the weather makes or breaks flights. Meteorology is one thing that many orderly pilots simply cannot control. Even on a sunny day full of blue skies, hidden dangers can lurk and throw aviators for a loop.

Next time you are taking to the skies and wondering if you know the ins and outs, remember this info for the most enjoyment out of your flight.

Pop-up Thunderstorms

Perhaps the most obvious threat to an airborne vehicle is a thunderstorm. Distinct from standard rain, thunderstorms bring wind, lightning, and even hail or tornadic activity. To make matters worse, not all thunderstorms can be seen as they are coming.

Instead, especially in the summer months, these thunderstorms will form out of 'thin air' and can grow into threatening cells or squall lines.

Satellite imagery of cumulus clouds quickly billowing into a large cumulonimbus thunderstorm off the coast of Cuba. Image Credit: GOES-16

Luckily, the atmosphere gives us clues as to where and when these thunderstorms may appear.

Relative humidity and PWATs (precipitable water) show how much water the air is holding that it may release. Moving air masses can form frontal boundaries, such as a cold front, that forces moist air upward, leading to towering clouds. These are a few of many examples.

Meteorologists continue to improve forecasting which regions are set to see conditions ripe for thunderstorms, and plenty of these resources are provided to pilots. The SPC (Severe Prediction Center) releases graphics up to 8 days out, detailing where severe thunderstorms may strike, and how severe they may be.

An SPC Thunderstorm Outlook featuring all 6 categorical risk levels, reaching the greatest possible risk 'High' on May 25th, 2021. Image Credit: SPC

Outflow Boundary

Outflow boundaries are some of Mother Nature's most fascinating phenomena (at least in the eyes of a weather radar). Let this image speak for itself.

The science behind this jellyfish-like loop is simple. When a thunderstorm forms, it drops rain and surrounding cool air to the ground (a downdraft). The downdraft is just gravity pulling this rain down from the skies.

Once this all hits the ground, it has nowhere to go but outward in all directions. As a result, a strong outflow of wind, also called a gust front, travels away from a thunderstorm in all directions.

What is being picked up on the radar image above is the debris, such as leaves or dust, being picked up from the surface by wind. It's a tell-tale marker of where an outflow is and where it's heading.

Associated with the outflow is a stark change in wind speed/direction, pressure, and temperature. This significantly impacts pilots because it can change their headwind, altimeter, or general feel associated with the aircraft.

The anatomy of an outflow boundary. Image Credit: MemphisWeather.net Blog

To make matters worse, outflow boundaries spark new lines of thunderstorms. The cool air rushing along the surface forces the warm, moist air that is currently in place upward. Rising moist air means — you guessed it — clouds, rain, and more. Sometimes, these newly-formed thunderstorms are stronger than the ones which started it all.

Wake Low

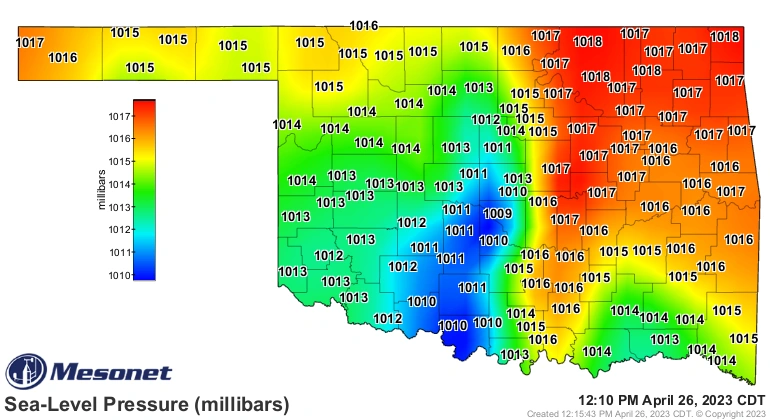

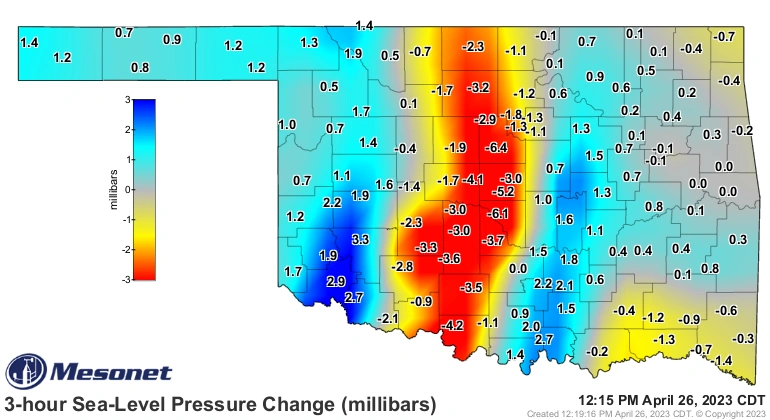

A wake low is easily understood by its literal name: a low pressure system that forms in the wake of a storm. But it is better understood with some science.

Showers and thunderstorms are formed by air that rises (an updraft). However, this air must sink back down to the ground at some point. It generally does so only 30-50 miles behind the storm complex. If the conditions are right, this sinking air warms as it nears the surface (adiabatic warming) and becomes less dense, thus causing a miniature low pressure system.

Because this low pressure forms so close to a comparatively-high pressure environment, a tight pressure gradient is formed. Air rushes from the storms towards low pressure, which can lead to high wind gusts.

What's significant is the strongest wind gusts of the day can be recorded after the storm has already passed. In fact, they can sometimes occur with blue skies. To a presumptuous pilot, what looks like a good post-storm flight is actually a catastrophic mistake.

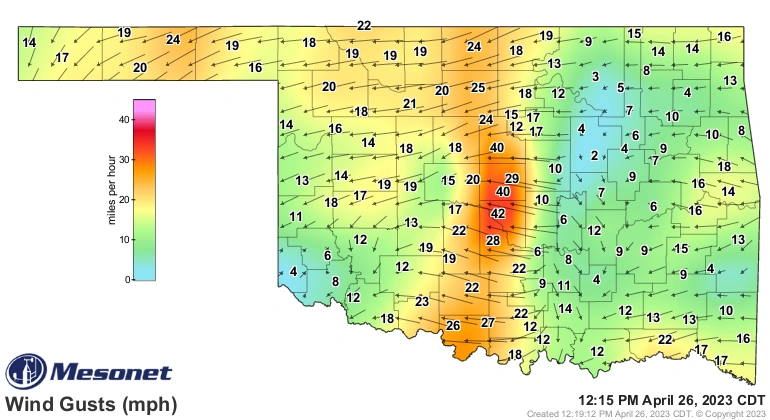

A series of images that demonstrate a wake low formation and the resultant wind gusts in Oklahoma in April 2023. Imagine the line of rain along the red-shaded region on the image furthest left. Image Credit: NWS Norman (via X)

Wind gusts upwards of 70 miles per hour have been recorded from wake lows in the past. Further, a wake low is partially to blame for the Seacor Power disaster of April 2021, where a large liftboat capsized off the coast of Louisiana and killed thirteen people.

Wind Shear

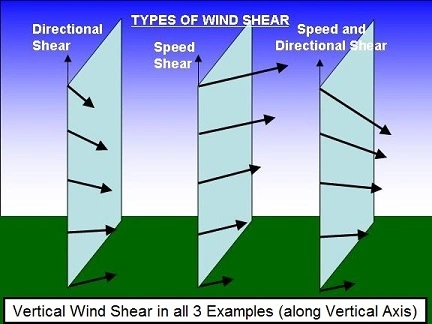

A rather well-known threat to pilots is wind shear. It is defined as the change in wind speed or direction in relation to altitude. Wind shear can be vertical or horizontal, localized or widespread.

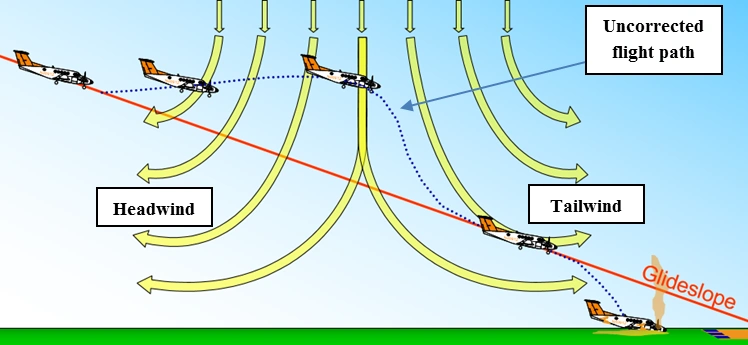

For aviators, the greatest problems with wind shear occurs by changing a plane's lift. A stronger headwind causes greater lift because more air is rushing past the plane's wings. However, if that wind direction changes to a tailwind in a short period of time, a pilot will have more difficulty adjusting altitude and speed. This is especially true when approaching for landing, as sudden changes in lift can (and have) had disastrous effects near the runway.

The potential result of localized wind shear when a plane flies through a downdraft. Image Credit: World Meteorological Organization

A small-scale wind shear event like this is most likely near a storm, where an outflow boundary may occur (See? Even the weather likes to repeat itself). Another possibility is at an airport near an ocean, where a sea breeze can lead to different wind direction over the water versus over land.

Frontal boundaries, such as cold fronts, force other air masses to move, causing shifts in wind directions where the two masses meet. Interestingly enough, wind shear is necessary for tornadoes to form and maintain their strength. At the same time, wind shear is detrimental for hurricanes. This distinction is a result of the different anatomy between the two commonly confused phenomena.

The various types of wind shear. Image Credit: NWS Turbulence

Dry Lines

Luckily, few pilots fly on a day where an active dry line is forecast. That's because it is arguably the most famous atmospheric setup in all of meteorology.

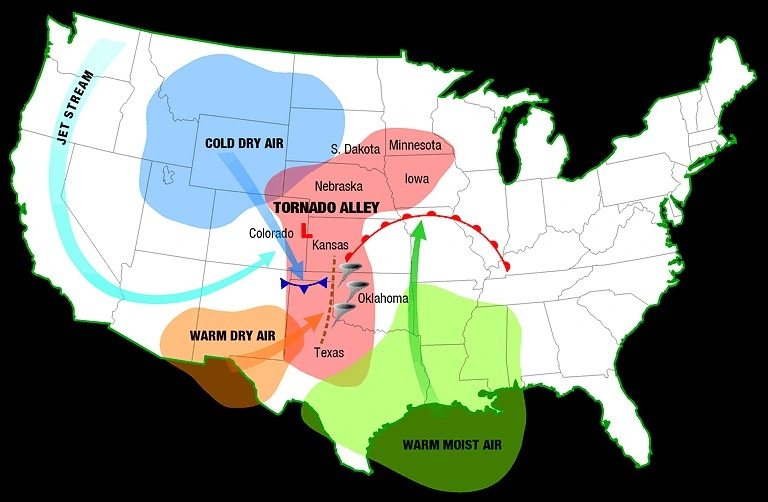

As opposed to frontal boundaries, which separate air masses of different temperatures, dry lines separate air masses of different moisture concentrations. This most frequently occurs between the warm, dry air of the desert southwest and the warm, moist air of the gulf of Mexico. The dry line is then set through Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas.

The setup that leans to a dryline setup, and consequently, tornado alley in the same region. Image Credit: NOAA

Dry lines, like every danger described in this article, is hidden to those who have not taken time to understand the weather. These are normally dormant until they are sparked, either by a cold front or some other trigger. Whatever the spark is forces the dry air to undercut the moist air, forcing it to rise. This leads to a rapid development of thunderstorms, and usually, tornadic supercells.

Dry lines are responsible for some of the worst tornadoes in U.S. history, including Joplin, Moore, and Jarrell.

Radar imagery of a stationary dry line (center) being sparked by an incoming frontal boundary (from left). The result is a explosion of thunderstorms in an instant. Image Credit: WeatherCurious Blog, Reddit user/ tWkiLler96

Dry lines are so well-forecast by meteorologists that enough cautions and warnings are issued to prevent pilots from venturing into the danger zone. However, its is evident this would lead to a tragic turn in an unsuspecting pilot's flight.

What You Can Do

As already mentioned, plenty of free, government-owned organizations provide bouts of information for pilots to better comprehend the weather. Many private companies make this information even more user friendly (hint — check out MyRadar's Aviation layer).

Pilots are also recommended to utilize the three different weather briefings: Outlook, Standard, and Abbreviated, from days out to less than an hour before the flight to hear the weather summarized by a trained meteorologist.

There is plenty more that pilots do to adequately train for the weather, but there is always something to learn when the atmosphere gets active.

*I would like to give a shout-out to those who inspired me to write this article at the Reading Aero Club. Founded in 1932, they are the nation's very first flight club and maintain a prestigious reputation to this day (in addition to being a great group of people). Check out their upcoming Career Fair at Reading Regional Airport (KRDG) on October 21st here: https://www.aviationcareerfair.org/